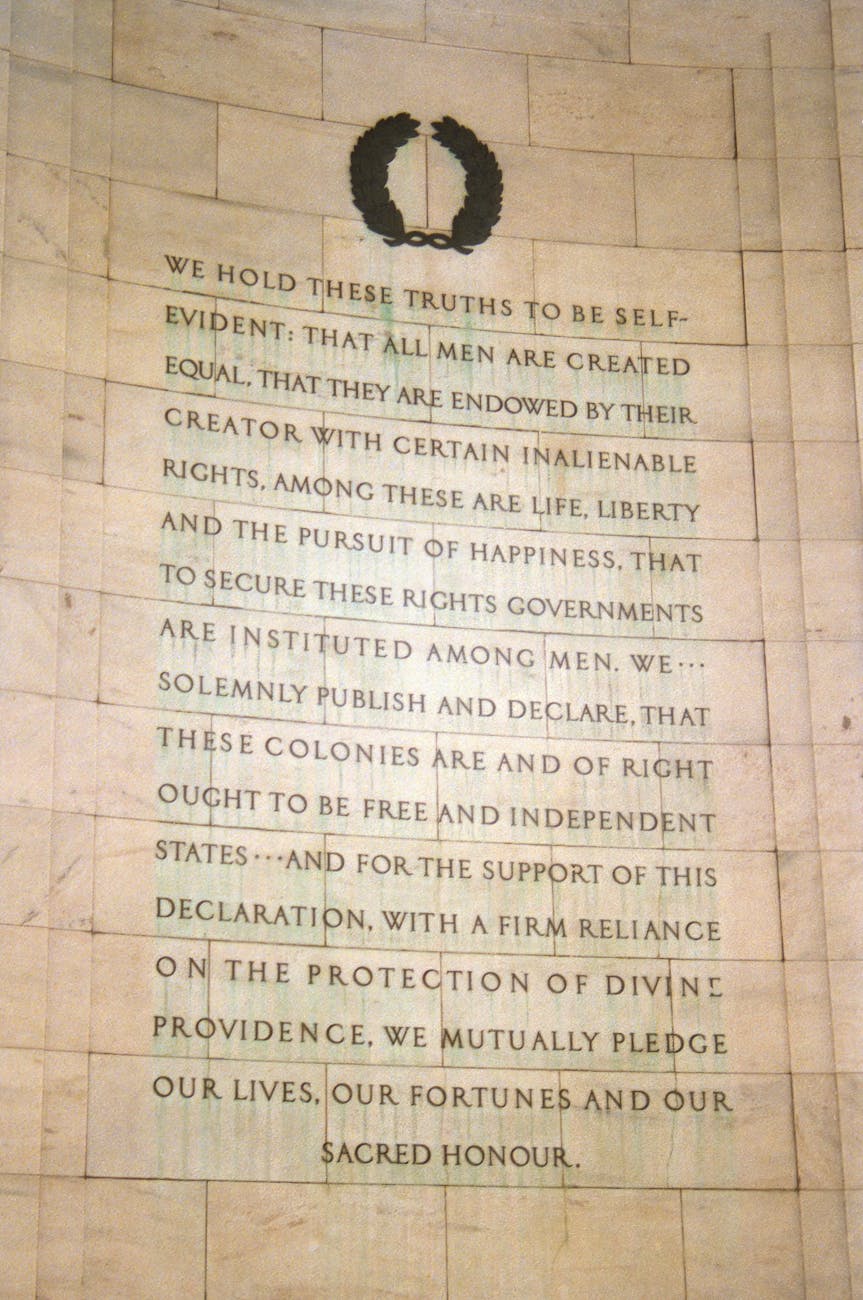

Having pronounced at length the achievements towards equality and liberty in the constitutional development of the United States, Chief Justice Roberts continued to say that these “landmark developments, carried forward the Nation’s ongoing project to make the ideals set out in the Declaration real for all Americans, in the never-ending quest to fulfill the Constitution’s promise of a “more perfect Union”.”[1] The content of his introduction to the 2025 Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary presents a coherent framing of the Constitution as representing the gradual realization of the ideals of the Declaration. What strikes me most, besides much else that is worthy of further examination in the Chief Justice’s statement, is that he framed these developments under the national ideal of unity, expressly borrowing phraseology from the Constitution’s Preamble.

For to the mind of the Founders the idea of “union” and of the “People” were quite distinct, leaving aside the question of their interrelation for a moment. Thus in No. 5 of The Federalist John Jay said: “weakness and divisions at home would invite dangers from abroad; and that nothing would tend more to secure us from them than union, strength and good government within ourselves”.[2] Thus, the notion of union is the guiding principle of federalism. To have a “more perfect Union” first meant that the absolute sovereignty of the states as it them existed be limited by a federal government supreme in its own jurisdiction. Indeed, the foreign model Jay cited as an example of this for the newborn American nation was that of the union of Great Britain, which reinforces what I have said. At the beginning of his paper, Jay quotes from Queen Anne’s letter to the Scottish Parliament.[3] Therein she exhorted the Scottish legislature to accept union with England, not that England after long ages past achieve Edward I’s iniquitous aim of abolishing the internal distinction and peoplehood of the Scots. Rather, so that in one state there be two peoples of the Scots and English within one new nation of the British, with their distinct internal arrangements preserved. She said: “It must increase your strength, riches, and trade; and by this union the whole island, being joined in affection and free from all apprehensions of different interest, will be enabled to resist all its enemies.”[4] Likewise, the arrangement established amongst the then thirteen United States abolished restrictions on interstate commerce, established common defense forces, whilst maintaining distinctions between ones obligations to his state and to the United States.

Madison himself observed that the Constitution’s Preamble was not itself intended to be binding, in a manner analogous to the non-binding preambles to British Acts of Parliament. He said: “Like resolutions preliminary to legal enactments it was understood by all, that they were to be reduced by proper limitations and specifications, in the form in which they were to be final and operative; as was actually done in the progress of the session”.[5] The “more perfect Union” in the Preamble is therefore a general idea indicating what the legal text provides for, in the federal structure of the United States government supreme in its own sphere over the states, but the states retaining their reserve of non-delegated authority.

What has this to do with the people? Are these not distinct ideas in the Preamble? Distinct, yes, but interrelated and recognized as such from the beginning. Chief Justice Roberts great predecessor John Marshall himself is authority for this proposition in McCulloch v. Maryland.[6] He began the dictum which I have in mind by first stating that at the enactment of the Constitution, the mode of proceeding chosen was by constitutional conventions at the level of the states. He continues, and I will quote at length,

“This mode of proceeding was adopted, and by the convention, by Congress, and by the State legislatures, the instrument was submitted to the people. They acted upon it in the only manner in which they can act safely, effectively and wisely, on such a subject – by assembling in convention. It is true, they assembled in their several States – and where else should they have assembled? No political dreamer was ever wild enough to think of breaking down the lines which separate the States, and of compounding the American people into one common mass. Of consequence, when they act, they act in their States. But the measures they adopt do not, on that account, cease to be the measures of the people themselves, or become the measures of the State governments.

From these conventions the Constitution derives its whole authority. The government proceeds directly from the people; is “ordained and established” in the name of the people, and is declared to be ordained, “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, and secure the blessings of liberty to themselves and to their posterity.””[7]

What the Chief Justice says here is that the people of America at large acted in the particular institutional arrangements of the separate legally sovereign states, but in order that they may act as the people of America each in their respective states. As such, an American is by the meaning of the Constitution even as originally enacted and interpreted in McCulloch, united to all those who are citizens of the United States, and thus subject to the United States, but legally subject also to his own local state. The first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment extended and clarified this reality.[8] The Nineteenth Amendment creatively interpreted the idea of equality the Founders proposed, and took it forward to achieve equal citizenship on the basis of sex, after it had been achieved (imperfectly) on the basis of race after the Civil War. It is, I think, to this initial meaning and subsequent greater realization of the meaning of the Preamble (as well as the Declaration) which the present Chief Justice, John Roberts, was referring to in his comments on a “more perfect Union”.

Indeed, he gestured to these constitutional provisions alongside the precedent in Brown v. Board of Education,[9]the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “among other landmark developments” towards achieving a “more perfect Union” by making real the ideals of the Declaration.[10] Thus we see the Chief Justice’s remarkable moral reading of the Constitution in his theory of American government. The document is interpreted textually precisely because the underlying moral ideals of American government are laudable. This moral reading seems to have two aspects from what I can see. First, that the people themselves are united in order that the ideals of the Declaration be enacted in the Constitution. Second, that the more perfect realization of these ideals in the Constitution itself secures the unity of the people. I submit that this second point only makes sense if read alongside Madison’s insistence that the final purpose of government is justice. “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It has ever been and ever will be the pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.”[11] Justice is equilibrium in human relations; it is harmony among persons in their respective stations amongst each other. The ideals in the Declaration seek to pursue the human good, and insofar as they do, they represent the ideal of justice itself to which the American Republic must strive. This conviction, I believe, underlies fidelity to the text of the Constitution. “A more perfect Union” is achieved in America by the contingent arrangements of federalism particularly suited to the character, geography, and history of that land. It is achieved also, and this is indispensable if the institutional arrangements are to work and have any human value, if justice is achieved in and amongst the people. Americans must do this by pursuing yet more and more the perfection of the ideal proposed by the Declaration. This is what I take Chief Justice Roberts to mean; his is a profound and moving vision.

[1] Chief Justice John Roberts, 2025 Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary (31 December 2025) 7 <https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/year-end/2025year-endreport.pdf> accessed 02 January 2026; U.S. Const. Preamble.

[2] John Jay, The Federalist No. 5 <https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed05.asp> accessed 02 January 2026

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] James Madison, Letter to Robert S. Garnett (11 Feb. 1824) in The Writings of James Madison (vol. 9, Galliard Hunt ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1910) 177. Available from the Online Library of Liberty at <https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/madison-the-writings-vol-9-1819-1836>

[6] McCulloch v. Maryland 17 U.S. (4 What.) 316 (1819)

[7] Ibid 403-404

[8] U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside”.

[9] Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 487 (1954)

[10] Chief Justice John Roberts (n1) 7

[11] James Madison, The Federalist No. 51 <https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed51.asp> accessed 02 January 2025

Leave a comment